China’s Journey To The Center Of The Earth

Men work with trucks at the Mirador mine of Ecuadorian Ecuacorriente, subsidiary of China’s … [+]

AFP via Getty Images

The recent $3 billion sale of Chile’s Compañía General de Electricidad to China’s State Grid Corporation brought total Chinese control of electricity transmission in Chile up to 57%. Similar PRC acquisitions and projects are currently being advanced in Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Honduras, Peru, and Columbia, where corporations are building hydropower, wind, and solar power stations. But China’s energy push into Latin America is not limited to infrastructure. This is fast becoming a multi-pronged approach that also includes the securing of critical minerals, particularly rare earth elements (REEs). The United States, meanwhile, is mum.

Beijing has invested over $180 million into Venezuelan nickel mining, and an additional $580 million into more general mining services. Similar deals are underway in Chile and Peru, which account for 55% of China’s copper. Chinese state-owned company Chinalco has a controlling interest in the Peruvian Toromocho and La Bambas copper mines, with another Chinese-backed mine in Ecuador. China’s Xinjiang TBEA has acquired a 49% stake in Bolivia’s lithium industry as well, and while lithium, like copper and nickel, is not a rare earth, it remains a key component of many electric vehicle batteries.

While China searches for REE plays in Latin America amidst its critical mineral push, it already claims a near-global monopoly on rare earth extraction and refining. REEs are the building blocks of 21st century technology and China has moved aggressively to take control of each stage of the supply chain, establishing infrastructure and co-opting regional markets and elites well in advance of other nations. The United States may be losing the race for the future before most of its citizens hear the starting pistol.

Right now, China is home to a staggering 30% of global REE mined ores within its borders, and makes up 80% of worldwide rare-earth processing production. Their investments into countries in mineral-rich Africa, Central Asia, and Latin America seek to heighten that number, allowing Beijing to become the global supplier of vital, strategic resources crucial to our technological progress and economic development. Rare earths are the oil of the 21st century.

Through various ventures launched since 2006, Chinese mining companies invested a total of $36 billion in Sub-Saharan Africa, and they keep building on. Abilities to do so derive from a history of anti-colonial political support and foreign direct investment throughout African nations. Beijing has significant investments in cobalt mining throughout the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where 60% of global cobalt reserves are found.

KOLWEZI, DRC: A miner collects small chunks of cobalt inside the CDM (Congo DongFang Mining) Kasulo … [+]

Corbis via Getty Images

While cobalt is not designated as a rare-earth, it is in the ‘critical mineral’ family with REEs and remains a primary ingredient of the ubiquitous lithium-ion battery. With its projects in the DRC, China now controls 72% of global cobalt refining capacity.

In South America and Southeast Asia, Chinese companies have captured large quantities of REE supplies and built significant mining infrastructure. Over half of unrefined heavy REEs imported to China come from Myanmar, while partnerships with Brazilian mining companies have yielded positive trade relations in Latin America. Greenland, another mineral rich region, saw Chinese corporation Shenghe Resources Holding Co. attempt to build an REE extraction facility at Kvanefjeld that would’ve produced 10% of the world’s rare earths, though. However, the venture was blocked by the environmentalist political party, Inuit Ataquit.

Like Russia with its natural gas supplies to Europe and Ukraine, the Chinese government has already demonstrated its willingness to use REEs supplies as an economic weapon. After the Japanese Coast Guard detained a Chinese fisherman near the Senkaku Islands in 2010, Beijing briefly shut down REE exports to Japan in protest. Using this leverage, China was able to eventually secure the release of its fisherman. This will not be the last time China presses its REE advantage to coerce its neighbors.

That geopolitical leverage could be used against the U.S. and its allies, if the west fails to acquire its own REE supply and refining infrastructure.

Recent efforts to bolster U.S. rare earth supplies began with Presidential Executive Orders 13817 in late 2017 and 13953 in late 2020, which authorized the Department of Defense to evaluate domestic mineral site expansion and declared over-reliance on Chinese REE processing to be a national emergency. The designations applied by the Trump administration continued into the Biden administration, where Executive Order 14017 ordered a major review into supply chains gaps.

The Mountain Pass Rare Earth Mine in California is the only integrated rare-earth extraction and processing facility in North America. However, that number is expected to rise given increasing federal and corporate interest. Australia’s Lynas Corp, the second largest global REE producer, was awarded $30.4 million by the U.S. Department of Defense to build a processing facility in Rio Hondo, Texas. Materials mined by Lynas, originally shipped to China, will instead be bound for the United States, where domestic companies will be responsible for refinement.

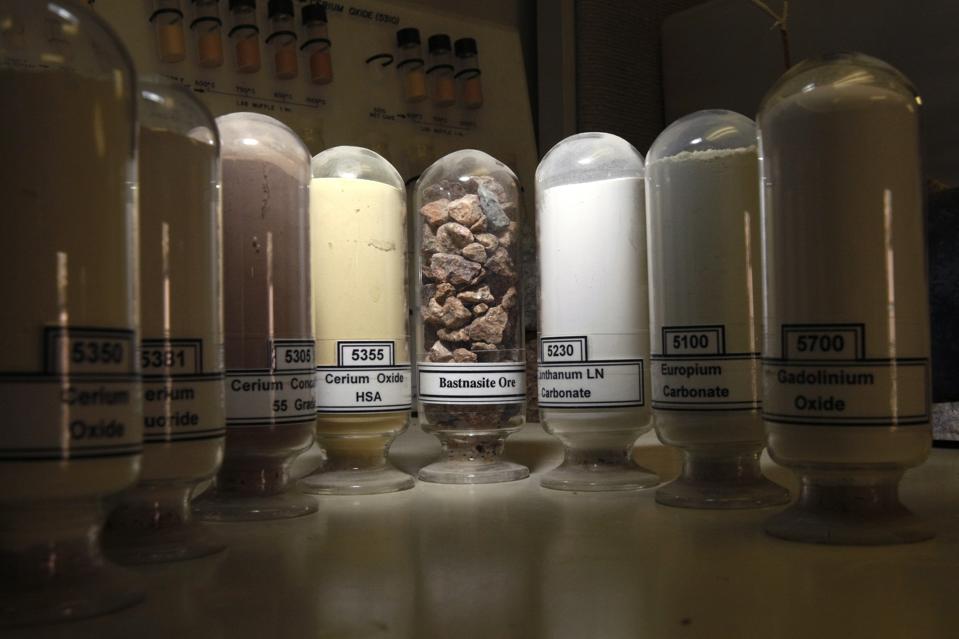

SEPTEMBER 11, 2009. MOUNTAIN PASS, CA. In the lab at Molycorp Minerals mine in Mountain Pass, CA, … [+]

Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Cooperation between the “five eyes” of the U.S., Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the U.K. is crucial, as well as additional joint ventures with Mexico, South American countries, and other key NATO and non-NATO allies. Yet, as the Biden Administration plans to diminish the U.S. and its allies’ dependence on Chinese REE capabilities, it needs to keep in mind the length of the supply chain and its defensibility, as well as the cost of transportation.

Rare-earth mineral extraction will likely create a competition between Washington and Beijing in the developing world, from Latin America and Africa across the Eurasian landmass. In this modern gold rush, for now, Beijing holds a strong early advantage. To catch up, American policy makers must treat the security of rare earth supply chains in the same way that we once treated our crude oil and natural gas imports in the pre-shale era: a matter of vital national security.

With Assistance From Liam Taylor