Come True Sees Straight Into Your Nightmares

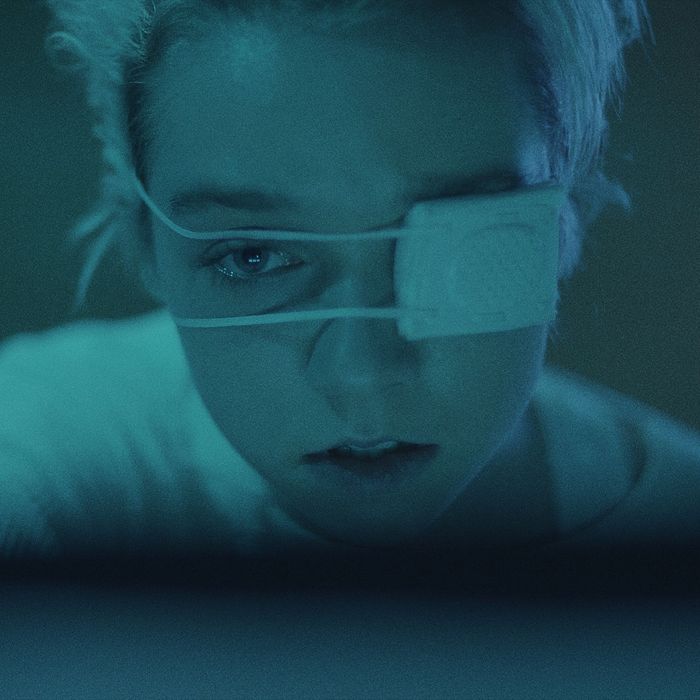

When I spoke to Anthony Scott Burns, the writer-director of the new sci-fi horror film Come True, I was in the midst of a heady bout of insomnia that, during the daytime, gave me the vague sensation that I was living inside a very boring video game. It turned out to be the perfect state of mind for our conversation: Come True, which follows an insomniac teenager named Sarah (Julia Sarah Stone) who joins a sleep study that turns sinister and surreal, is both about dreams and unfolds like an impressionistic, slow-burn nightmare. The indie stuck with me for several weeks after I saw it — I couldn’t shake its haunting imagery, its muted sense of foreboding, and its hypnotic tone, which lulled me into a sort of dream state as I watched it.

Part of what makes Come True so effective is the sense that Burns — who shot and edited the film, and also co-created the unnerving John Carpenter–esque soundtrack under the name Pilotpriest — is completely in control of his vision, and is confidently strapping you into a bleak theme-park ride straight to the center of your own psyche. Burns shows us very few concrete details about the clearly traumatized Sarah, outside of the fact that she rarely sleeps and spends her nights away from home, tormented by nightmares as she tries to snuggle up on a slide at a public park. But he implants us directly into her twisted subconscious, which features shadowy men with glowing eyes, floating bodies, and all other sorts of depraved images that feel both terrifying and increasingly familiar. Slowly, it becomes clear that Come True itself is structured and shot like a grim, blue-black dream: Sarah’s mother and best friend disappear with no explanation or follow-up; Sarah quietly wanders her small town’s empty streets alone for most of the film, save for a few strange and possibly age-inappropriate dalliances with Jeremy, one of her sleep scientists (Landon Liboiron); there are gaps in time, location, and plot that go unremarked upon. The effect is more poetry than straight narrative, and it’s all the freakier for it.

Come True also pays wanton homage to all sorts of existing pop culture, with visual and auditory references to everything from Tron to Twin Peaks to Rodney Ascher’s sleep-paralysis documentary The Nightmare to Carpenter’s The Prince of Darkness. It all amplifies the disturbing sense that you’ve been here before — you’ve seen a movie a little bit like this, you’ve walked down this silent suburban street, you’ve witnessed these men in your dreams, you’ve woken up gasping, convinced that there’s someone standing in the corner of your room. Before Come True’s March 12 release, Burns and I got on Zoom to have a slightly dorm-room-stoner conversation about the collective unconscious, whether we should be paying attention to what the glowing-eyed men in our nightmares are trying to tell us, David Lynch, the pop-culture feedback loop, and the film’s divisive ending.

I’ve been thinking about this movie a lot. And ironically, I’ve had a really hard time sleeping for the past two weeks, so I’m really out of it right now. I apologize!

I’m always struggling [with sleep]. So that’s good!

Where did the idea for this film first come from?

The first inklings for the story popped into my brain when I saw this video on YouTube about Berkeley developing a technology that could translate brain wave activity into imagery — to see through brain waves and to see how the brain reacted to images, and then interpret what our eyeballs received. It was this really blurry, AI weirdness. And I thought, If they can do this from our ocular nerves, couldn’t they do it from dreams? Coupled with the idea that, in sleep paralysis, so many people shared similar iconography that overlapped, [that] was a really good starting point for entering this world. What’s on the other side of dreams? There’s something more at work than simply a mass [hallucination]. It was about, how do I tell that story in a way that interests me?

For me, making movies is more about resting on emotion than a perfect screenplay. Much like the theory of this film, and Carl Jung’s theory of collective consciousness, I wanted to make a movie that ran on my subconscious, developed from my subconscious, but knowing that a lot of things I was pulling from were from our collective subconscious. So it was really trying to make a horror movie that supported Carl Jung’s theories, and then people would watch the films and see themselves in it — things that we all fear together.

Let’s go back to the study. How similar or different is the existing technology to the technology in your film, which lets scientists view the study participants’ dreams?

From what I saw, they have the [sleeping] cap, but it’s very different. They’d show what the person was watching, and then show their interpretation, and it was interesting to see that it was very much like [how] Google’s AI interprets images. That really stood out to me. There’s a shot where it shows Steve Martin, and it shows the face your [brain] sees, but it’s nothing like Steve Martin. It’s very rudimentary and inaccurate — this idea that our brain works like AI and tries to, from all of the things you’ve seen before, tell you what it is. It’s the same in that it’s a piece of technology that allows us to see what our minds see, but that’s about the depth of the closeness. Ours is wildly sci-fi. But in the next ten years, we may be able to see our dreams.

When did you start to become fascinated with these themes — Carl Jung and dreams and sleep paralysis?

Probably my entire life. [Laughs.] Dreams are highly intriguing. It’s where we work out our issues, who we are, what we fear. When I was about 8, my mom passed away, and I had sleep paralysis. I saw a shadow sitting at the end of my bed. At first, I was horrified. Because in paralysis, you can’t move, and I thought it was my mom, but I couldn’t talk to her. It was this grief merged with fear. And I realized if this thing turned around and looked at me — weirdly, I always knew it would have glowing eyes. And then it just went away. Years later, I saw the doc The Nightmare, and that’s what it’s about— this idea that we’re having a mass hallucination on that level, and we’re all seeing the same thing. Why not be intrigued by that?

One of my favorite cartoons as a kid was Alice in Wonderland, and it inspired the dreams in this movie a lot: the artistry, the idea of spotlights and everything else fading into blackness. A nightmare narrative that takes you on a journey of nonsense, continuously shifting based on what the protagonist is feeling at that time, is a huge inspiration for the film. I have terrible nightmares, too.

Do you still have sleep paralysis? And what do you dream about now?

I haven’t had sleep paralysis since that bout with my mother. But in terms of nightmares, endless. Super realistic, always moving forward, like in the movie, like a carnival ride that takes me places. To some degree the film is based on my own nightmares, but I put in icons of other people’s dreams that I knew, from research, they’d recognize as well. Luckily I’ve had people reach out and say, “Hey, I’ve seen that in my dreams! Why? Why are you doing this?”

What have people noticed?

I saved a few of those responses but I don’t have them with me — just, “That scene is directly out of my dream.” And I don’t know what they’re talking about in particular, but these icons, the shadow people, that’s how we all see them. There’s a moment when one of the shadow people is surrounded by teeth, and the closing of the claws, church icons, bodies of water. Another interviewer told me that the opening shot of the mountain, he’d had that dream, floating toward that mountain. I was like, “Well, okay, good!” Which further supports Carl Jung’s theories, that we all have the same genetic fear memories that we’re swimming in. And we gotta figure those things out to be complete people.

It’s interesting that you mentioned The Nightmare, because I thought of that a lot while watching. At what point in your process did you see that? How did it influence the movie?

I saw it probably a year after I started — I’ve been working on it for about six years. And it solidified this notion that we’re all seeing the same stuff. And that really freaked me out. Science can come up with a realistic reason why: Our ancestors, if they saw an animal in the middle of the night, their eyes probably glowed, so that icon burned into our genetic memories as, “Don’t ever go to a shadowy thing with glowy eyes, you’ll get eaten.” So that’s probably where it comes from, but who knows. I like the idea that there’s something more at work, and to toy with that. The Nightmare made me realize it was so prevalent, and pervasive, with people who had sleep paralysis. But in terms of filmmaking, I pulled from many different things to make the movie look the way it does.

I want to get into all of those influences. Something I instantly thought of while watching it was that website and meme from a while back, “Ever Dreamed This Man”? Do you know what I’m talking about?

I think I know — the Creepypasta thing? I’m sure that had something to do with it, too. [I show him the photo.] Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah! [His dog starts barking loudly.] Cooper! Shh. That’s Agent Cooper.

I knew there was Twin Peaks in here!

Of course. I couldn’t escape it. Anyway, the face guy — that’s the thing. When you talk about dreams, there are these things that get under all of our skin. That’s what I really wanted to do, to listen to what gets under my skin, put it into the movie, and hope to God that it’s what gets under everybody’s skin. I said to people, “This movie is like therapy to me, in that I allowed it to be what it wanted to be.” There’s a modern striving for cinematic perfection, and I wanted to not listen to that. Like, I know that might not make the best narrative sense, but it makes dream logic sense, and it’s coming to me in a very honest way. For instance, I would argue that Sarah is the only real person in the movie. Everyone else is a construct of the media that I grew up with. And me questioning and sort of toying with these weird ideas of what influenced us all — this collective consciousness, our thought processes. What got Sarah to where she is now, based on that culture?

It’s really interesting to think about the collective unconscious as it applies to dreams, but also as it applies to pop culture, and the way it subtly influences all of us as we consume it together.

It’s much more influential than artists ever want to admit. Because they get in trouble when it comes to censorship: If you portray something as cool, or normal, will it [become] normal? All of a sudden you get an entire generation of people thinking that the behavior of, [for example] Jeremy, is normal. I really wanted to examine that. I think some people really have problems with the characters in my movies sometimes, even when they do things that the character is plainly suggesting that they want to do. Like, “Jeremy is the love interest?” Yes, but he’s a piece of junk. He’s always been a piece of junk.

What do you mean?

Have you seen Joe Dante’s Explorers? ’80s movies in general — I grew up with movies where children and teenagers, especially the boys, acted in really questionable ways. I wanted to play with that in Come True, and have a main character act in ways that were unacceptable, to show the intent and go through with it. In Explorers, they develop this technology to travel to outer space as kids, and the first thing they do is that they float up to a girl’s window and they spy on her in her bedroom. It’s like, “What are you doing?!” That’s really completely pervasive in ’80s media and culture. And it’s little things like that, that I wanted to explore in my movie. And I wanted Sarah to have to come head to head with all of the things I’d been influenced by.

Like Lynch, and Tron —

Weirdly, Tron! A big influence on me. But such a different kind of movie than I wanted to make. But, yeah.

It’s fascinating to think about consuming these things and then dreaming about them and then making movies about the dreams that pay homage to the original movies — it’s this sort of feedback loop.

Oh, yeah. I’m also an artist, on the side, and now it’s interesting — art is even worse now of a feedback loop than it ever has been. It’s kind of bizarre. And people don’t even see thievery as a negative. I used to see new and exciting pieces of artwork that really blew my mind, and the dawn of the internet really scared me —you’d see all of these wild pieces, and it was really amazing, and now you see the copy of the copy of the copy of the copy. I haven’t been able to escape it. And in fact, I decided to embrace it. This movie isn’t an ’80s movie, in no way, shape, or form. If you took it back in time, people would say, “What is this?” But it’s built from all of the things I’ve been influenced by. I just can’t escape them. So I just decided, I’m going to explore that. And within the narrative itself, sort of try to figure out what it is and why I’m drawn to certain things.

And the film feels like a dream, which adds another layer entirely.

Yes! The film is a dream. It’s a film dream. As a filmmaker and someone into movies of that era, it’s what you would dream. That was the idea!

Do you want people to be on drugs while watching this movie?

[Laughs.] You know, I don’t suggest it. That might hurt. I once had people over when I was younger, and these kids had all done acid at a party, and I had Fire Walk With Me on. It wasn’t good for them.

That is very stressful to imagine.

Yeah. It wasn’t good. I wouldn’t recommend it.

Are you a lucid dreamer? This movie felt to me specifically like a lucid dream.

Yeah. I’m getting better at it. You know, one day, when I was working on this film, I was walking down the street, and a guy walked up to me, completely normal, just a normal college student. He said, “Hey man. Come here for a second. You know this is all a dream, right?” And he just walked off. That really hit me.

Oh my God.

For no reason! My whole thing is, we don’t know anything. So I just want to be a weird conduit to the things we don’t know, put out a piece of art that felt like my dreams. The good and the bad … It makes me believe in Cinema Jesus. Telling us what to make as movies. You just listen to Cinema Jesus and he tells you the right ideas.

You think there’s, like, a deep subconscious oracle dictating to us?

I can’t say no! When someone comes up and says, “This world’s all a dream,” while I’m working on a movie about it, I can’t say no. There’s too many things that point towards it. This is why we love movies like The Matrix. There’s so much that points toward the evidence of the Matrix, as opposed to not. This movie exists in the realm of, “Is it possible? I guess.”

Did you see Rodney Ascher’s newest doc, A Glitch in the Matrix?

I haven’t yet. Apparently there’s crossover with Come True.

Yeah, it’s kind of freaking me out. To that point, there are holes in the narrative of the film. Can you talk to me about resisting the need to explain things? Like, not explaining what’s going on with her mom, where’s her friend, how does she get between these disparate locations?

There’s a longer cut of the film where a lot more is explained. But I found that in the screenwriting process and in the finished film, if you go into the drama of what’s happening at her house, it only serves to pull us further away from the feeling of being in a dream. In a dream, you’re one place one second, you’re one place another second. As long as there’s a theme that makes you go there, that’s how dreams work. It just felt the most natural to do it that way, to keep the mystery stronger — the closer we could get it to feeling like a dream, the better it created emotions.

The only place you can do this is in independent film, and specifically low-budget independent film. Because it’s really hard to get those decisions past a committee. So why not make something experimental in this realm? When I get asked to make something for Marvel, I’ll start answering questions. [Laughs.] But even WandaVision isn’t answering all of the questions! I think people are starting to embrace not wanting answers. But for a while there, media was pretty on the nose. This is reactionary against that.

The film feels really tonally consistent and cohesive. Do you credit that to just being hands on about every single detail — writing, direction, shooting, editing, soundtrack?

Maybe to its detriment. Had we had the money for the kinds of craftspeople who could help in that realm, I’d love to have them onboard. But our ambitions were wildly bigger than our budget. The only way to do it was through brute force. It’s really hard to convince people to give you millions of dollars in the current market.

What was the budget?

I’m not gonna tell you. [Laughs.]

Well, I think it’s important to contextualize.

There’s the real budget and then there’s the “once you finish everything” budget. I’ll just say it hovers around $1 million CAD. I couldn’t have made this movie outside of Canada. We have a support system. It’s why David Cronenberg exists. It’s hard to convince people to make weirdo genre movies.

[Spoilers below for Come True’s ending.]

I want to talk about the ending. I was a little confused by it, which I know is the point. Can you talk about what you wanted the feeling of the audience to be at that point?

I wanted the feeling of the finale to be the feeling that man left me with on the street. I was confused why that man walked up to me and said that to me at that exact moment, and I wanted people to come away from the film with that same confusion. It’s not an accident that the message stays onscreen for a long time. It’s not that I’m an idiot. People should think about the calculated tone that we talked about, in terms of the ending, and go, “What are the chances that Anthony, all of a sudden, got really stupid?”

Do people think that’s what happened, that you got “stupid”?

Some people! Someone wrote, “I’ve never seen a more inept ending in my life.” It’s because they think I just went, “It’s all a dream!” It isn’t. Much like the film is a cinematic dream, it’s something that takes place in what I believe Carl Jung is talking about, the dream that we all live in. So the message might not be for Sarah.

It’s for us?

Yeah.

It is a sort of derided trope

It’s what you’d expect from a movie about dreams! Come on.

But it did feel too easy. So that’s not exactly what I thought was happening. Did you anticipate that reaction?

Right, if it feels too easy, it probably is. I knew some people would think that. That’s okay. But you hope someone else standing next to them will say, “I don’t think so.” It’s the same feeling I’d come away with when I’d see something like Lost Highway in the theater. Someone would say, “Oh, that’s a hunk of shit.” And somebody would say, “That’s the best thing ever.” I’d rather be making movies that some people think are a hunk of shit and some people love, than someone saying, “That was just okay.”

I did feel uneasy and sick after.

Yay!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.