In Mississippi, Black residents are desperate to get vaccinated. But they face access barriers.

JACKSON, Miss. — On the last Saturday in January, Johnny Thomas paused as a train snaked through the heart of Glendora, Mississippi. The accompanying roar reverberated through the predominantly Black Mississippi Delta town with a population of fewer than 200 people.

“Ever heard of the other side of the tracks?” Thomas, the town’s mayor, asked. “That’s us.”

In a community where the nearest hospital is more than 20 miles away, the phrase stretches past the proverbial. More than 50 percent of residents live in poverty.

Lately, Thomas has felt pushed even further to the margins. No coronavirus vaccination sites for the general public are operating in Tallahatchie County, where Glendora is. The area’s only hospital, Tallahatchie General, doesn’t expect to have vaccines until mid-February. The nearest state-run drive-thru vaccination clinic is in neighboring LeFlore County, 30 miles away.

“We couldn’t find two people to get that far without it being a hardship,” Thomas said.

Even for those who have the means to travel, appointments go quickly. Last month, Thomas, who is 67, spent almost an hour trying to reach someone on the state’s vaccination hotline hoping to book a slot for himself, only to meet a busy signal.

The pandemic has hit Mississippi’s impoverished, rural and primarily Black communities hard. And disparities are present in the state’s vaccinations. The state’s Black residents are vastly underrepresented among Mississippians who have been vaccinated so far. Mississippi has the highest percentage of Black residents in the nation — 38 percent — but only 17 percent of those who have received the shots have been identified as Black. That’s one of the worst racial gaps in the country.

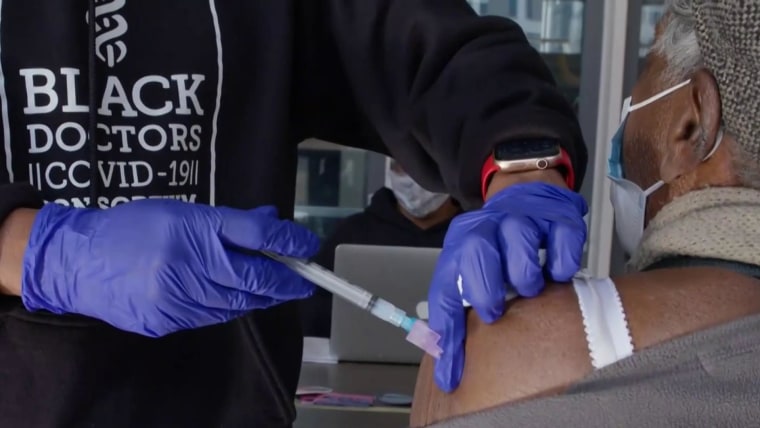

Mississippi’s leaders have focused on a hesitancy to get the vaccine in communities of color to explain this gap, and they have devoted resources to partner with prominent Black community leaders, many of whom have gotten the vaccine on camera in an effort to overcome concerns about its safety and effectiveness.

But over the past several weeks, local doctors, community leaders and even state officials say it’s become increasingly clear that many Black residents want to get vaccinated — they’re just hitting roadblocks that have prevented them from doing so. Lasting scars from slavery and segregation — including a long history of unequal treatment of Black residents by the state government — touch many aspects of life in Mississippi, leading to racial disparities in access to health care that mean Black residents often have to travel farther for medical check-ups. Only 4 of the state’s 10 counties where residents are least likely to live in a household with a car have a vaccination site this week. All of these counties are at least 60 percent Black.

“What recently I’ve heard is that the balance has changed and actually, the access issue is a bigger issue than the trust,” Dr. Thomas Dobbs, Mississippi’s state health officer, said at a news briefing last week. “We will try to address both of those as aggressively as we can.”

For the poor and communities of color, access barriers can snowball. There’s little advance notice of vaccine appointments for people in low-wage work so they can make arrangements to take time off, provided they have paid leave at all. Going online is the fastest way to book an appointment for the state’s drive-thru sites, but Tuesday’s announcement on social media from Gov. Tate Reeves, a Republican, of 30,000 new appointments was most likely missed by residents without reliable internet access who can’t check as often for available slots.

For most of January, only two state-run vaccination sites were available in each of the state’s nine health regions. Mississippi’s most populous county, Hinds, which includes Jackson and where more than two-thirds of residents are Black, lacked a drive-thru vaccination site until Jan. 21. State health officials attributed the initial absence to planning challenges.

On Monday, Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba said current vaccine measures don’t take into account disparities that disproportionately affect residents in the predominantly Black city.

“Whether intentionally or not, it is discriminatory in this sense: that it depends on a level of privilege. It requires [someone] to go online to set up an appointment. That would depend on someone having computer or Internet access,” he said. “A lot of locations around the state have been drive-through locations. That depends on someone having transportation to do that.”

Do you have a story to share about Covid-19 vaccinations in the South? Contact us

While 21 state-run vaccination hubs are almost equally split across nine geographic zones, the ease with which communities can access the resources needed to make appointments is not. Dr. DeGail Hadley, a physician in Bolivar County, Mississippi, said some of his patients living in the rural town of Shelby have to pay $20 for a 15-minute ride to his clinic in Cleveland, the county seat. He called the cost “astronomical” in an area where well-paying jobs were hard to come by long before the pandemic devastated the nation’s economy.

“For patients who don’t have many resources, that’s a lot of money,” Hadley said. “Some may have to come up with the decision to cut back on buying food or cut back on getting medicine.”

Although two vaccination sites are available in Bolivar County, a limited supply of doses means some locals could have to travel to sites an hour or more away, Hadley said.

New outbreaks could further fracture the fragile network that helps Hadley’s patients survive. Bolivar County has the highest rate of new infections in the Mississippi Delta. He worries that neighbors who volunteered to give friends or elderly acquaintances rides in normal times might consider it too risky now. One solution, he said, would be using a mobile unit to bring vaccinations to apartment complexes and rural neighborhoods.

For Evelyn Washington, a retiree in Rome, Mississippi, transportation problems are acute. About twice a month she runs errands for neighbors who can’t get out of their homes easily because of health challenges, or who don’t have access to reliable transportation. No one’s asked her for a ride to a vaccination appointment yet, but she’s willing to step up.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Rome is in Sunflower County, adjacent to Bolivar County in the Delta. Hardships are prevalent throughout Sunflower, which is 74 percent Black and where 32 percent of residents live in poverty. But there are days when Washington feels her community, which is 5 miles down the road from the state penitentiary, is forgotten. The town doesn’t have a grocery store and residents often have to travel to the county’s larger towns of Indianola and Ruleville to shop for fresh food.

“It’s just rural and it’s just hard during this time,” she said.

Mississippi has gained significant ground since early January, when the state initially ranked second to last in vaccination rates. As of Monday, Feb. 1, the state was 31st in the nation in the share of the population vaccinated, according to an NBC News analysis.

But Mississippi’s recent improvement in administration rates hasn’t touched all corners of the state. No vaccination sites are available in Sharkey County or Issaquena County, which have both seen a higher Covid-19 infection and death rate than the state as a whole.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

In Issaquena County, where roughly 60 percent of the population is Black, the death toll has been unsparing. Four out of 1,000 residents have died from the virus, but only 37 of the county’s 1,400 residents have received the vaccine, or about 3 percent — less than half the state’s average of 7 percent. There are no primary care physicians in Issaquena County, according to a 2016 report from the State Department of Health, which layers on another barrier to making sure residents are protected from the virus.

John Fairman, the CEO of Delta Health Center, which focuses on providing health care to low-income patients, has received only enough vials of the vaccine to offer appointments at one of its clinics, in Bolivar County.

“The absence of supply is so overwhelming it makes it hard to properly plan,” Fairman said.

Last month, workers added 1,000 names to the center’s waiting list.

Fairman said front office workers have been “worn thin” with requests for the vaccine. They’ve turned away frustrated visitors hoping to get vaccinated as a walk-in. The center quickly ran through the initial 308 doses it had available for the public. Eighty percent of those who showed up for their first dose identified as Black. He sees the demand as an encouraging sign that the state’s racial gap will narrow as community health centers like his are able to provide more doses in the region.

“We are serving the population that folks are saying is challenging to get to,” Fairman said. “I would submit to you if community health centers had the vaccines that number would look radically different.”

State health officials have said that the state’s vaccine allocation strategy takes risk factors, like race and age, into account by targeting doses to partners providing care to vulnerable groups. Dobbs said the majority of the state’s vaccine allotment has gone to partners like hospitals, private clinics and community health centers that focus on underinsured and low-income populations.

“We have been aggressively trying to address these disparities,” Dobbs said, “but there are also some existing health care infrastructure challenges in some places in the state, like Issaquena.”

In Tallahatchie County, Thomas, the mayor of Glendora, was finally able to book a vaccination appointment for Feb. 15 in LeFlore County, about 30 miles away. On some days, he said, the only open slots he saw were on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, a three- or four-hour drive away.

He’s still lobbying to bring a site closer to home. He hopes the Biden administration’s goal of creating dozens of federally managed vaccination stations by the end of this month will reach his community.

“They’re working on making 100 sites,” he said. “We should be one of them.”